Under pressure: The reality of Australia's hospital emergency departments

Kimberly Grabham

06 January 2026, 1:00 AM

Walk into Royal Adelaide Hospital's emergency department on any given day and you'll find a chaotic but functioning system. The wait might be 30 minutes. There are specialists on site. Advanced diagnostic equipment hums in the background. Ambulances queue at the door.

Now picture Wilcannia. The Multipurpose Service there technically provides 24-hour emergency care. But as of November 2025, if you present between 7pm and 7am, you must first call ahead. Staff will decide whether to come in. The doors aren't always open.

This is the reality of Australia's two-tiered emergency care system, and it's crucial to understand from the outset that our dedicated doctors, nurses, and healthcare workers are not the problem.

They are the heroes holding a fractured system together through sheer determination and professionalism.

What's failing isn't the quality of our medical professionals but the system that asks them to do the impossible with inadequate resources, chronic understaffing, and policy settings that haven't kept pace with demand.

Every statistic about wait times and bed shortages represents healthcare workers fighting against overwhelming odds to provide care they know Australians deserve.

If you've felt like emergency department waits are getting longer in cities, you're not imagining it.

The data confirms what millions of Australians already know from painful personal experience.

In 2024-25, there were 9.1 million emergency presentations to public hospitals across Australia.

Half of all patients were seen within 18 minutes, which sounds reasonable until you realise that overall, only 67 per cent of patients were seen within the recommended time for their triage category.

Perhaps most troubling is that for patients requiring admission to hospital, wait times have exploded.

The time in which 90 per cent of these patients complete their emergency department visit has increased by over 6.5 hours in recent years, from 11 hours and 43 minutes in 2018-19 to a staggering 18 hours and 23 minutes in 2022-23. Let that sink in: nearly a full day in an emergency department before being admitted to a hospital bed.

While city hospitals grapple with overcrowding, rural Australia faces a fundamentally different problem. Emergency departments barely function or don't exist at all in many communities. Wilcannia's situation exemplifies the crisis.

The temporary change to after-hours access, requiring patients to call ahead between 7pm and 7am, will remain in place until at least 31 January 2026.

NSW Health frames this as ensuring patients receive safe care during the summer holiday period. The reality is simpler and more stark: there aren't enough staff to keep the doors open around the clock.

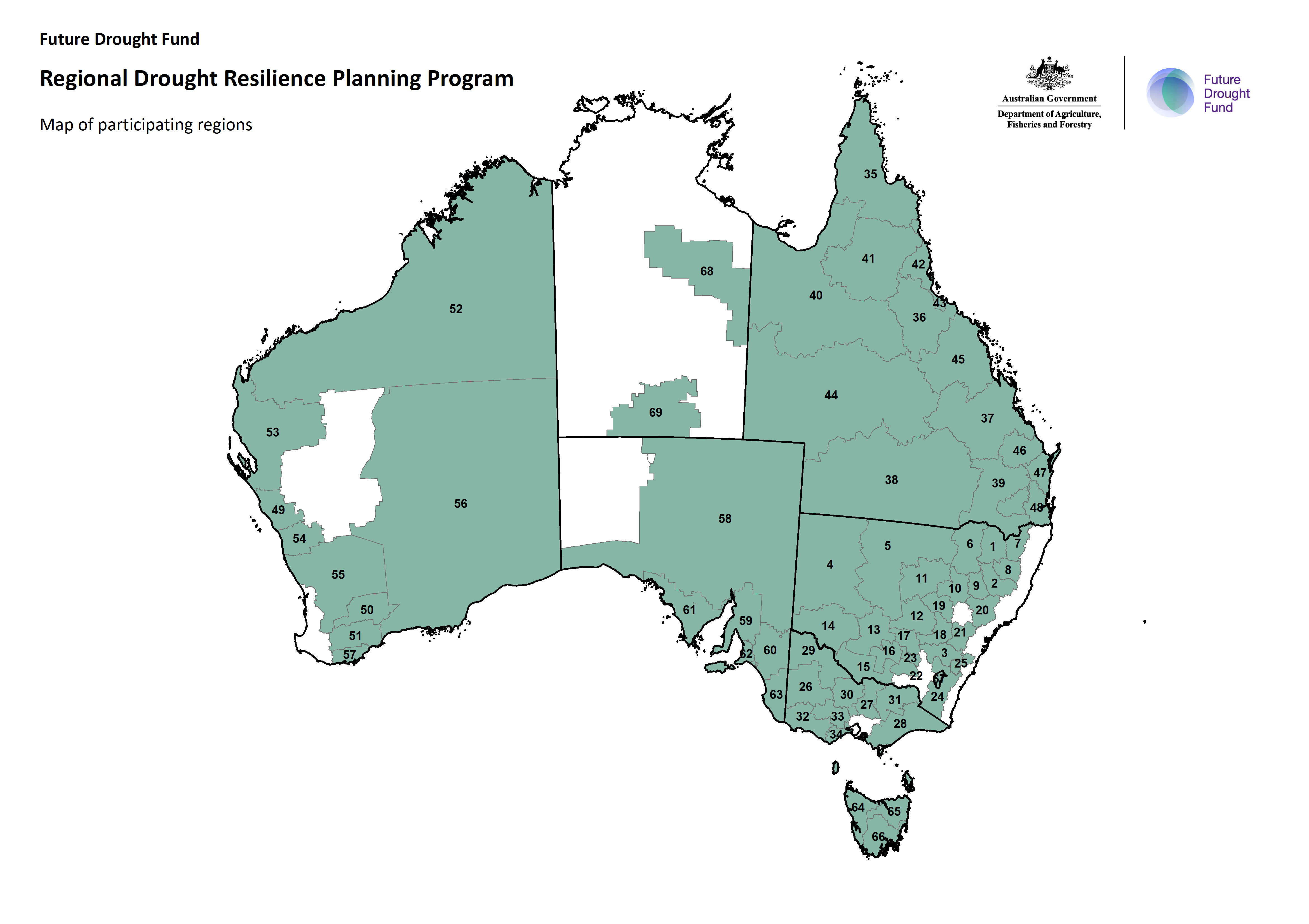

And Wilcannia isn't alone. Across rural and remote Australia, more than 400 hospital-based emergency care facilities serve communities, managing over one third of Australia's emergency presentations.

But staffing shortages are catastrophic, as high as 85 per cent for specialist trainee roles, 66 per cent for junior medical officer positions, and 22 per cent for senior decision-making roles in rural and remote emergency departments.

Small rural towns suffer the most.

Research from the University of Wollongong found that the greatest workforce shortfalls aren't in the most remote areas but in small rural towns. These communities have three times fewer doctors per capita than metropolitan areas, and twice as few nurses and allied health workers.

The nurses and doctors who do work in these communities are performing miracles daily, often managing complex cases without the backup and resources their metropolitan colleagues take for granted. They're making clinical decisions in isolation, covering multiple roles simultaneously, and working extended hours because there's simply no one else to share the load.

Emergency departments operate on a five-category triage system that determines how quickly you need to be seen. Resuscitation means immediate care for life-threatening conditions, and almost all these patients are seen instantly.

Emergency category means care within 10 minutes for imminently life-threatening conditions, though only 64 per cent are seen on time. Urgent means within 30 minutes for potentially life-threatening situations.

Semi-urgent means within 60 minutes for conditions requiring medical attention but not immediately life-threatening.

Non-urgent means within 120 minutes for minor illnesses or injuries. The system works well for the most critical cases.

The problem is for everyone else, and everyone else constitutes the vast majority of presentations.

But in rural areas, this sophisticated triage system often becomes meaningless. Over 60 per cent of small rural hospitals have only on-call doctors, not staff physically present in the facility. Nurses frequently must assess and manage patients without onsite medical backup, making split-second decisions that would have a team of specialists consulting in a metropolitan hospital. These rural nurses demonstrate extraordinary clinical judgement and courage, but they shouldn't have to work in such isolation. Radiology and pathology services may only be available during business hours, if at all, meaning even routine investigations can't be performed when emergencies happen overnight.

The workforce crisis manifests differently depending on where you live. In metropolitan hospitals, the challenge is managing volume. Liverpool Emergency Department in Sydney receives more than 90,000 presentations annually. Despite impressive recent improvements, halving average treatment time for emergency patients from 18 to 9 minutes, the sheer numbers create relentless pressure on staff who are already working at capacity. These healthcare workers are achieving remarkable results not because the system supports them adequately but because they refuse to let patients down despite overwhelming circumstances.

In rural areas, it's about basic coverage. Australian rural emergency care facilities don't always have 24-hour medical cover, emergency specialist involvement, or onsite diagnostic resources that are mandated for accredited emergency departments in cities. Rural generalists and international medical graduates form the predominant medical workforce, and there simply aren't enough of them. The Australian College for Emergency Medicine's data shows that emergency medical staff in regional areas manage a greater volume of presentations per full-time doctor compared to their metropolitan peers.

In large metropolitan hospitals, the ratio is one doctor to 1,062 patient visits. In small and medium regional hospitals, it's one to 1,736. Those rural doctors are seeing nearly two thirds more patients each, and they're doing so with fewer resources and less specialist backup.

One of the biggest threats to emergency department function is bed block, when patients stay in hospital beyond their expected discharge date because appropriate care isn't available elsewhere. In NSW alone, 1,151 patients were stuck waiting in hospitals for federally funded aged care or NDIS support in the September quarter of 2025, an increase of 54 per cent over the previous year. Dr Peter Allely, president of the Australian College of Emergency Medicine, minces no words about the consequences for metropolitan EDs: when every bed in emergency is occupied by patients who should already be on a ward, the next person who needs urgent care can't be seen safely. This isn't a failure of hospital staff but of the broader health and aged care system that leaves hospitals holding responsibility for patients who need different care settings.

For rural hospitals, bed block creates a different crisis. Small facilities lack the capacity to hold multiple patients awaiting transfer or discharge. A single patient blocking a bed can effectively shut down emergency capacity for an entire region. Rural patients are more likely to have extended stays in emergency departments awaiting inpatient care than those in metro hospitals, leading to poorer outcomes through no fault of the dedicated staff caring for them.

In metropolitan areas, if one emergency department is overwhelmed, ambulances can divert to another facility 15 to 20 minutes away. This mobility doesn't exist in rural Australia. From Wilcannia, the nearest alternative emergency department is in Menindee, 36 kilometres away. The next closest is Broken Hill, 216 kilometres distant. For someone experiencing a medical emergency at 2am, those distances can mean the difference between life and death. Many rural residents are forced to travel vast distances to access diagnostic services, specialist care, and treatment. This requires leaving behind family and community support networks, along with substantial time and expense for travel and accommodation.

Behind the statistics is a bitter political dispute between federal and state governments over who's responsible for the crisis, while the healthcare workers caught in the middle continue providing care regardless of which government is technically responsible for funding it. State health ministers point to the surge in Commonwealth bed block, patients waiting for federally funded aged care or NDIS support. NSW Health Minister Ryan Park has been blunt about the serious consequences for our state hospitals, from wards to surgeries that can't be conducted to people waiting for beds in the emergency department. Federal Health Minister Mark Butler counters that urgent care clinics are making a difference and that the government is working towards a comprehensive National Health Reform Agreement. Dr Allely's perspective cuts through the political positioning: state and federal governments need to come together to get to the core of the problem. Meanwhile, rural hospitals and their communities are largely absent from this debate. The problems facing Wilcannia or similar small towns don't fit neatly into urban-centric political discussions about bed block and ambulance ramping.

The federal government's flagship response has been rolling out Medicare Urgent Care Clinics, now 87 nationwide with 50 more planned. These bulk-billed facilities handle urgent but non-life-threatening conditions, and more than 1.2 million Australians have used them. The government touts their success in reducing emergency department pressure, but the evidence is nuanced and the model is almost entirely urban-focused. While one million urgent care clinic visits sounds impressive, context matters. There were 9 million emergency department presentations in 2023-24. Even if every visit prevented an ED presentation, which isn't necessarily the case, it represents only about 11 per cent of total demand. More critically, urgent care clinics offer little to rural Australians. The model requires sufficient population density to be viable and competes with general practices for the same scarce pool of GPs and nurses. The Mount Gambier urgent care clinic recently went into liquidation amid staff shortages, a cautionary tale for rural areas already struggling with workforce.

Despite system-wide pressure, some metropolitan hospitals have achieved remarkable improvements through the dedication and innovation of their staff combined with targeted support. In NSW, Liverpool ED halved average treatment time for emergency patients from 18 to 9 minutes over the past year through the extraordinary efforts of their team. Westmead ED reduced similar times by over a third. Nepean ED increased the percentage of patients transferred from paramedics to ED staff on time from 65.1 to 82.2 per cent. These successes show what's possible when healthcare workers receive adequate resources and support. NSW has invested $31.4 million in Hospital in the Home programmes, allowing over 3,500 additional patients annually to be cared for at home rather than occupying beds. The $15.1 million Ambulance Matrix provides real-time hospital data to paramedics for better patient distribution. Such sophisticated systems are impossible to replicate in places like Wilcannia, where the challenge isn't optimising patient flow but simply having staff available.

Underneath all policy debates lies a fundamental problem: workforce shortages affecting all of Australian healthcare. By 2025, Australia faces a shortage of 100,000 nurses. Small rural towns have the lowest number of nurses and allied health care workers per capita. The maldistribution worsens with remoteness, and healthcare worker shortages are notably more severe in regional Australia, where 21 occupations are exclusively in shortage. The government has announced additional funding to train more GPs and nurses, but training takes years. Today's shortages reflect decisions made or not made a decade ago. Meanwhile, universities like Wollongong are making a difference. UOW medical graduates are 50 per cent more likely to work in regional or rural areas than graduates from other medical schools, with nearly a third working in rural areas within 10 years of graduating. But even this success story can't bridge the massive gap fast enough.

Wilcannia's after-hours model, call first and staff might come, represents a middle ground between full service and complete closure. But across Australia and globally, the trend towards rural emergency department closures is accelerating. The viability of many rural hospitals is uncertain. There's a serious threat to rural after-hours, urgent, and emergency care due to lack of investment and critical health resources. Some facilities have been forced to make the impossible choice: provide unsafe care with inadequate staffing or limit services and leave communities exposed. Healthcare services in rural and regional areas across Australia are facing ongoing challenges in health worker recruitment, as Wilcannia's temporary change to after-hours access explicitly acknowledges.

Both Australia and New Zealand's public health systems are funded and delivered on the basis of universal access to healthcare, regardless of location. In practice, this principle has not delivered equity. Rural residents have poorer health and shorter lives than those in urban areas. The data shows stark health inequities according to geographic location. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, who make up a significant proportion of many rural communities, face compounded disadvantages. Rural communities have considerably higher rates of emergency department utilisation and hospitalisation than urban peers, not because they're choosing emergency care over primary care but because emergency departments are often the only healthcare available, particularly after hours.

For metropolitan residents, the advice is familiar. Use alternatives when appropriate, considering your GP, urgent care clinics, or telehealth for non-emergencies. Understand that triage means long waits often indicate others need care more urgently, the system working as intended. Be prepared by bringing medications, medical history, and something to occupy your time. For rural residents, the advice rings hollow. Alternative services often don't exist. The nearest GP might be 100 kilometres away. Telehealth requires reliable internet, far from universal in rural areas. And being prepared for a wait assumes the emergency department is actually staffed when you arrive.

Multiple approaches are needed, recognising that metropolitan and rural challenges differ fundamentally. For metropolitan areas, we need expanded hospital capacity with more beds and staff, improved patient flow through Hospital in the Home programmes, better discharge planning to prevent bed block, coordinated federal and state responsibilities on aged care and NDIS, and continued innovative programmes that have shown results. For rural areas, we need sustainable funding models that recognise the economics of rural healthcare, targeted workforce recruitment and retention incentives, investment in rural medical training with explicit rural placement outcomes, technology solutions like telehealth backed by reliable infrastructure, community-based models that leverage local strengths, and recognition that rural facilities need different standards appropriate to their context. The Australian College for Emergency Medicine has launched a Rural Health Action Plan providing strategic vision for strengthening emergency medicine in rural areas, focusing on workforce, research, collaboration, and service provision.

Australia's emergency departments are simultaneously performing heroics and struggling under unprecedented strain, but the nature of that struggle varies dramatically by location. Our medical professionals in metropolitan hospitals are working overtime, treating more patients than ever, achieving impressive results for the most critically ill through sheer determination and skill. Many have reduced wait times through innovative programmes and extraordinary dedication. Yet system-wide pressures continue to intensify, not because these healthcare workers aren't working hard enough but because the system itself is fundamentally under-resourced.

Rural hospitals face an existential crisis. It's not about optimising patient flow or reducing ambulance ramping. It's about having staff present. It's about keeping doors open. It's about maintaining any emergency capability at all. The nurses and doctors who choose to work in rural Australia deserve our deepest respect and gratitude. They're providing care in circumstances that would break many people, often with minimal support and recognition.

As NSW Health Minister Ryan Park cautioned while acknowledging metropolitan improvements, I don't want us to get ahead of ourselves because these figures, while encouraging, will fluctuate. Our EDs continue to grapple with record pressure and demand, and we mustn't forget that. For rural Australians, the pressure isn't just record-setting but potentially life-threatening. When the nearest alternative emergency department is over 200 kilometres away and your local facility requires calling ahead to see if staff are available, record pressure understates the severity.

The fundamental question facing Australia's health system isn't whether it can survive. It's whether we're willing to give it the resources, workforce, and policy coordination it needs to thrive, and whether we're willing to recognise that rural Australia requires fundamentally different solutions than metropolitan areas. Until federal and state governments move beyond jurisdictional blame games, until rural healthcare gets the targeted investment it desperately needs, and until we acknowledge that universal healthcare access means different things in different places, the crisis will continue. Our healthcare workers will keep showing up, keep providing exceptional care, and keep holding the system together. The question is whether we care enough to give them the support they need before more rural emergency departments follow Wilcannia's path from 24-hour service to call-ahead only to closure.

If you're experiencing a life-threatening emergency, always call 000. For urgent but non-life-threatening conditions in metropolitan areas, consider contacting your GP, an urgent care clinic, or telehealth services. For rural residents, check your local hospital's current operating hours and after-hours protocols, as these may have changed.