Where the rivers meet the dead

Kimberly Grabham

16 September 2025, 2:00 AM

The mournful sound drifted across the still waters of the lake like nothing Major Thomas Mitchell had ever heard before, a wailing song that seemed to carry the weight of the world. It was 1835, and his exploring party had been following the Darling River north for days, mapping country that no European had ever seen. Now, as they stood on the shores of what he would name Laidley's Chain of Ponds, that haunting melody made his blood run cold.

Mitchell knew what it meant. The women were singing for their dead.

Just hours earlier, what should have been a simple resupply mission had gone horribly wrong. Two of his men had approached the water's edge with a kettle, needing fresh water for the evening camp. The local Barkindji people, who had been watching the strange procession of white men and horses with growing alarm, moved to investigate.

Mitchell's account of what happened next would be the only version to survive, but even his sanitised official report couldn't hide the horror of Australia's frontier reality. A kettle was grabbed. One of his men was struck down with a club. In the chaos that followed, two Barkindji men were shot. As the Aboriginal people fled into the water, more shots were fired. A woman carrying a baby on her back fell dead in the shallows.

The song that haunted Mitchell's dreams was the sound of a community mourning its first victims of European "exploration."

This was the bloody beginning of Menindee's recorded history—a place where two worlds collided with devastating consequences for one of them.

The Barkindji people had lived around these ephemeral lakes for thousands of years, following seasonal patterns that turned an apparently hostile desert into a productive homeland. They called the main lake "Minandichi," and to them it was the centre of a complex network of seasonal camps, trade routes, and sacred sites.

To Mitchell, it was simply an obstacle on his journey to map the continent for the Crown.

The explorer's party retreated quickly after the massacre, but the damage was done. Word spread through the Aboriginal networks that the white men brought death wherever they went. By the time the next European expedition arrived nine years later, led by Charles Sturt, the relationship between the races had already been poisoned by fear and violence.

Sturt's 1844 expedition established a base camp at Lake Cawndilla, using Menindee as a staging post for their ambitious journey into the heart of the continent.

They were searching for an inland sea that existed only in geographical theory, but their presence established European interests in the area. Soon after, the Darling Pastoral District was proclaimed, and Aboriginal people found themselves suddenly declared "trespassers" on their own traditional lands.

The transformation was swift and devastating. By 1849, Alexander McCallum had taken up the "Menindee" pastoral lease, establishing the first European claim to the area. In 1851, government surveyor Francis McCabe mapped the lower Darling River, officially naming the locality "Minnindia"—a bastardised version of the Aboriginal name that would later become Menindee.

By 1852, Thomas Pain had arrived with his wife Bridget and children, building the shanty hotel that would become the legendary Maiden's Hotel—the second-oldest pub in New South Wales and destined to serve one of Australia's most famous exploring parties.

That party arrived on 14 October 1860, travel-stained and exhausted after weeks of pushing north from Melbourne. Robert O'Hara Burke and William John Wills had accepted the Victorian government's challenge to cross the continent from south to north, racing against a South Australian expedition for the glory of being first to reach the Gulf of Carpentaria.

Their stay in Menindee would prove to be one of the most fateful stops in Australian exploration history.

Burke was an impatient man, driven by ambition and the fear that his rivals might beat him to the prize. Against all advice, he decided to press on into the unknown interior despite the approaching summer heat. The local Aboriginal people, their numbers already decimated by disease and displacement, watched the heavily laden expedition depart with a mixture of curiosity and foreboding.

What Burke and Wills couldn't have known was that they were walking into one of the most perfectly orchestrated disasters in Australian history. Their decision to push ahead with a small advance party, leaving the bulk of their supplies at Cooper Creek, would doom them to become martyrs rather than heroes.

The two explorers did reach the Gulf of Carpentaria, becoming the first Europeans to cross the continent from south to north. But their triumph was short-lived. On the return journey, weakened by malnutrition and tropical diseases, they found that their support party at Cooper Creek had departed just hours before their arrival. Burke and Wills died of starvation and exhaustion in the desert, their bodies later found by rescue parties who had started searching months too late.

Their companion, John King, survived to tell the tale, but only after being discovered in a state near death, cared for by local Aboriginal people who showed more compassion than the expedition's own supply party.

The grave of Dost Mahomet, one of the camel drivers who died during the expedition, still stands outside Menindee—a lonely reminder of the human cost of 19th-century exploration.

His headstone is one of the few physical monuments to the diverse group of men who participated in that doomed journey: Englishmen, Irishmen, Germans, and Indian camel handlers, all united in their pursuit of fame and discovery.

But Menindee's role in the Burke and Wills story was just the beginning of its complex relationship with European settlement.

The town that grew up around Pain's hotel became a crucial depot for the paddle steamer trade that transformed the Murray-Darling river system into Australia's highway to the interior. Wool from vast stations like Kinchega—which covered one million acres and ran 143,000 sheep at its peak—was collected by steamers and transported thousands of kilometres to markets in Adelaide.

The Kinchega operation represented the pinnacle of 19th-century pastoral efficiency. Steam engines pumped water to irrigate vast paddocks. Artesian bores supplemented the uncertain Darling River supply. Local Aboriginal people were employed as shepherds and station workers, adapting to a new economy that had destroyed their traditional way of life but offered the only available means of survival.

The massive woolshed, built in 1875 from corrugated iron and river red gum, processed six million sheep over its 92-year operational life. At its peak in the 1880s, it employed 26 blade shearers working in shifts around the clock during the season. The woolshed still stands today, listed on the Register of the National Estate as one of Australia's most significant industrial heritage sites.

But the paddle steamer era was always precarious, dependent on river levels that could change dramatically from year to year. Steamers sometimes became trapped at Menindee when the Darling dropped, forcing captains and crews to wait months or even years for the next flood to free them. By the 1920s, when the railway reached the district, the romance of river transport gave way to the reliability of overland freight.

The town's population declined steadily through the 20th century, but Menindee found new purpose as the gateway to one of Australia's most important inland water systems. The Menindee Lakes scheme, developed mid-century, created a system of nine large but shallow lakes contained by weirs, levees, and channels. The system now supports more than 220,000 waterbirds and provides crucial water security for communities across the Murray-Darling Basin.

Today's Menindee carries the weight of all this history in its dusty streets and faded buildings. The Maiden's Hotel still serves meals and drinks to travellers, much as it did when Burke and Wills stopped for their last comfortable night before heading into the desert. The ruins of Kinchega homestead tell stories of both Aboriginal displacement and European adaptation to an unforgiving landscape.

The modern town faces challenges that echo its troubled past: a declining population, limited economic opportunities, and the ongoing effects of cultural disruption that began with Mitchell's expedition in 1835. A 2009 study comparing Menindee with nearby Wilcannia found that both communities experienced similar social problems, but Menindee's more integrated population and lower crime rates meant it received less attention from government services—a mixed blessing that reflected the complex legacy of race relations in outback Australia.

The statistical reality of modern Menindee reveals a community that has found ways to manage the social pressures that overwhelm other outback towns. Its domestic violence rate of 20.6 per 1,000 residents, while still concerning, is significantly lower than Wilcannia's 93.5 per 1,000.

Perhaps the most significant truth about Menindee is that it represents both the tragedy and the possibility of Australian reconciliation. The mournful song that haunted Major Mitchell in 1835 was the sound of a culture mourning its first encounter with European violence. Nearly two centuries later, the same area hosts collaborative programs between Aboriginal traditional owners and government agencies to manage the lakes system that supports both human communities and wildlife.

The site where Burke and Wills camped beside Pamamaroo Creek, still marked today, reminds visitors that exploration has always carried human costs. The Aboriginal people who helped John King survive after his companions died understood something about this harsh country that the European explorers never learned: that survival depended not on conquest, but on adaptation, cooperation, and respect for the land's own rhythms.

The waters of Menindee Lakes still rise and fall with the seasons, supporting millions of waterbirds whose migrations connect this inland oasis to wetlands across the continent. In drought years, the lakes become mudflats that reveal the bones of ancient river red gums. In flood years, they become inland seas that support recreation, tourism, and the dreams of those who see hope in the desert.

The truth about Menindee's crime history isn't found in police statistics or newspaper headlines, but in the recognition that violence was a structural feature of European settlement from the very beginning. The real crime was the assumption that one people's exploration was more important than another people's existence. What followed—displacement, poverty, social disruption, and intergenerational trauma—were predictable consequences of that original violence.

Today's Menindee struggles with those legacies while building new stories of cooperation and adaptation. The town where two worlds first collided in blood has become a place where different communities work together to manage one of Australia's most important water resources. It's not a perfect solution to the problems created by history, but it represents something more hopeful than the mournful song that echoed across the waters nearly two centuries ago.

NEWS

SPORT

RURAL

COMMUNITY

VISIT HAY

VISIT BALRANALD

VISIT OUTBACK NSW

EVENTS

LOCAL WEATHER

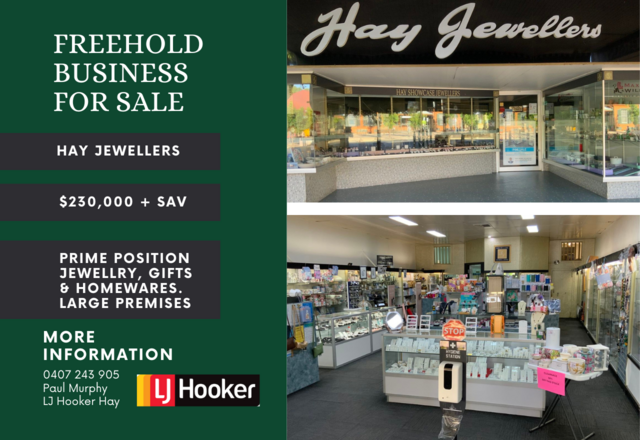

FOR SALE

COMMERCIAL PROPERTY