Underground War: Native Title vs. Home Ownership in the White Cliffs Dugouts

Krista Schade

16 October 2025, 7:00 PM

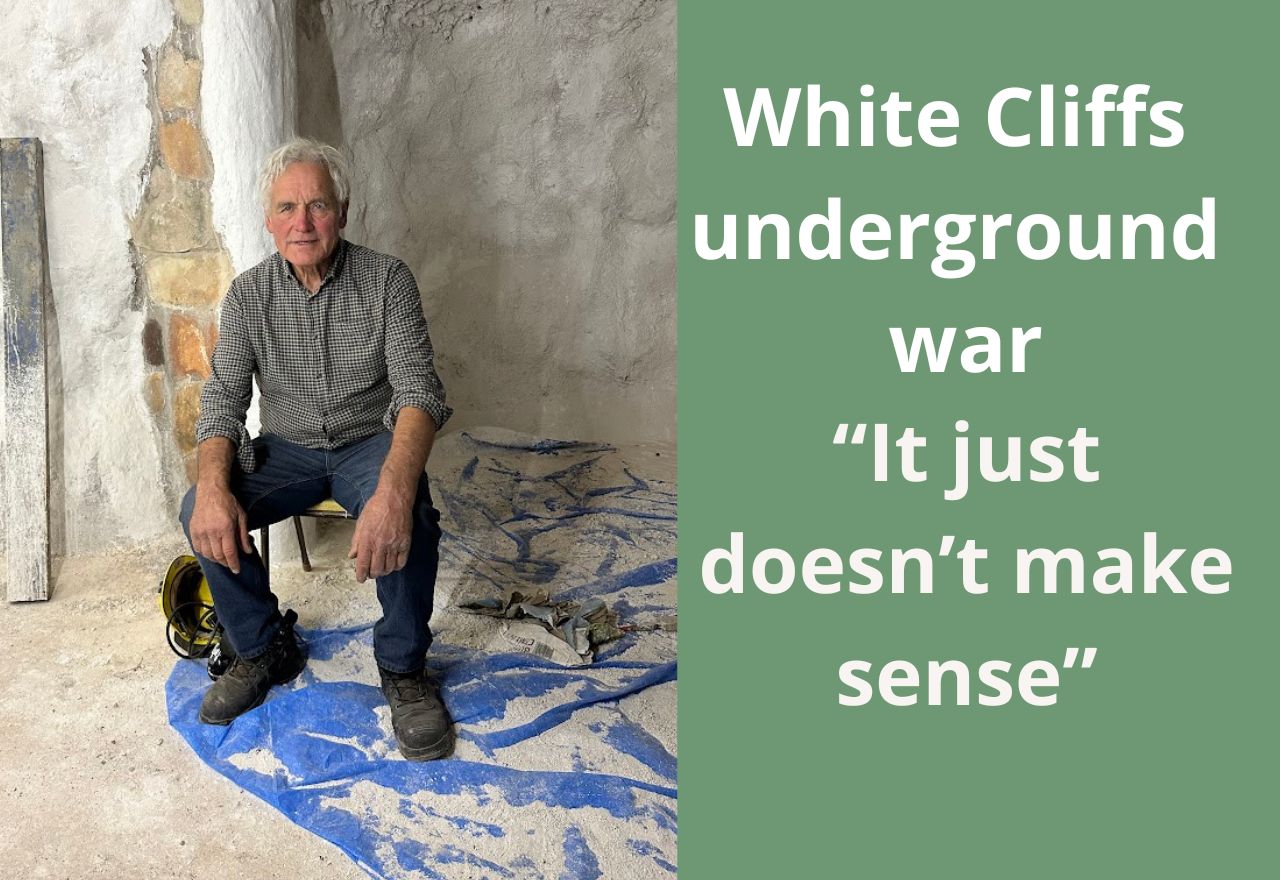

Dugout resident Ken Harris says the White Cliffs land dispute "doesn't make sense."

Dugout resident Ken Harris says the White Cliffs land dispute "doesn't make sense."White Cliff dugouts are some of the most unique homes in the country, but the underground residents say the stress of ongoing ownership issues is affecting their health and stifling new businesses.

In short:

- The White Cliffs dugout residents are facing a land tenure dispute that is stressing the community and preventing investment in over 120 unique underground homes.

- The community was promised freehold title by the NSW Government, but a 2015 Federal Court determination confirming Native Title rights for the Barkandji Corporation made this promise legally impossible.

- The NSW Government instead offered mandatory leasehold tenure—viewed by residents as a devastating setback—that does not reflect market value and includes a restrictive First Right of Refusal for the Barkandji Corporation.

- The uncertainty and "red tape tie up" mean residents cannot secure finance, put down roots, or make safety improvements like fire escape tunnels, causing potential businesses (like a mechanic) to go begging.

- Despite the NSW Crown Lands website claiming residents were granted "permanent security in 2021," residents strongly dispute this, stating the perpetual leases were not finalised until late 2024, and many remain unsigned under fear of losing their homes.

It the far west of NSW, where summer temperatures scorch the land above ground, living in dugouts has been common since the 1900s and now more than 120 such homes exist.

The ongoing land tenure dispute at White Cliffs, NSW, is a deeply complex problem, but behind the Native Title legalities are real people, and decades of frustrated community expectations. As expected, when homes and businesses are threatened, emotions run high.

Ken Harris has lived in White Cliffs for many years and is one resident who cannot make sense of the multi-layered red tape, which is binding up the outback town

“All this government money being spent on new roads, putting reticulating water, electricity, and the lot, and then you're giving somebody the opportunity to bulldoze it in,” he said, referring to the flurry of grants announced recently, and the need to give a regional Aboriginal organisation the first offer on any dugout sale.

“They also get public money to buy that dugout in the first place. It just doesn't make sense. And then there's the aerodrome expansion - $5.7 million on that - but they're arguing that the point about whether or not we can put in a fire escape for a dugout.”

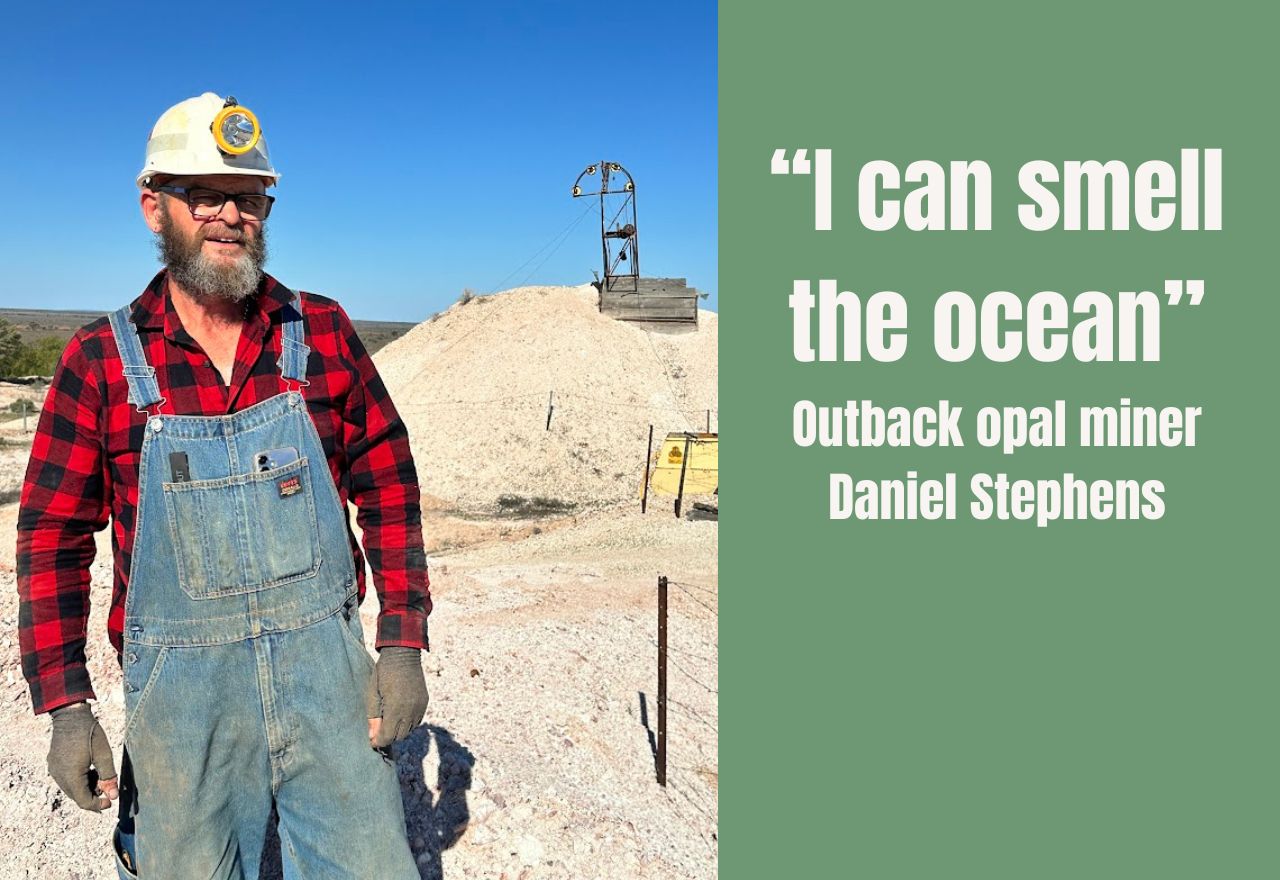

Despite growing up in Broken Hill Daniel Stephens fell in love with White Cliffs as a child and has been spending time learning the craft of mining around his role as carer of his aging parents.

A qualified diesel mechanic, Daniel wants to buy some land, build a workshop above ground and live underground in a dugout underneath, but the ongoing uncertainty means he can’t take the financial risk of setting up a business and a home.

For the community, it means having access to a mechanic goes begging.

“I could have my small mechanical business, come metal fabrication or whatnot,” Daniel explained. “I've got five children that I'm thinking of in the future as well. But I can't really lay out a big wad of cash or I can't go to the bank and borrow any money because it’s all up in the air.”

““I came to White Cliffs because I love the place and want to put down roots. I found a dugout home site that would suit me and my small business, and I’m ready to buy - but the process isn’t like buying a normal freehold block. Before I can move ahead, I have to give formal notice and then wait to find out whether another party wants to take the block instead. In practice, that means weeks of uncertainty where I can’t make plans, book trades, or secure finance with any confidence. If that other party decides to buy, I miss out - even though I’ve found the block, negotiated terms, and want to invest in the town.”

“I’m not asking for special treatment. I just want a fair way to buy a place, improve it, and contribute to White Cliffs. The current system makes that really hard.”

Ken’s youngest daughter Claudia Harris says the complicated system of land tenure is robbing families or the dream of home ownership.

“In this day and age, when it's so hard to be able to get an affordable home, you would think there would be flexibility for people that want to do their own thing to create a home, but it's like we've overcomplicated it to the point that it's unaffordable.

“It's not only the interest rates and the prices and the property developers and whatever, it's also the red tape tie up.”

Daniel sums up the frustration dugout residents are feeling.

“And it's always hard when it's, you know, 200 people saying, ‘can someone listen to us?’ We're not Parramatta. We're not Botany Bay. There's not 30,000 people saying, can we get an answer? There's just a few.”

The history of the White Cliffs dispute

The years-long conflict centres on the town’s unique residential dugout properties where long-term residents say they have been let down by Governments on all levels. Despite being assured of future freehold title by the NSW Government, locals are now being offered leasehold tenure, which is bound up by Native Title requirements and red tape.

Residents say that the NSW Government made continuous, and documented, assurances of conversion to freehold title, with some evidence dating back to 2004.

At the same time freehold assurances were being made by the NSW Government, the 2015 Federal Court determination of a native title claim lodged by the Barkandji Corporation, representing the region’s First Nations people, brought to a halt the dream of dugout home ownership.

The determination confirmed non-exclusive rights and interests to Barkandji Corporation, rights which include the unlimited ability to take and use natural resources, and the right to take and use water for personal, domestic, and communal purposes within the determined area. This means that the Barkandji Corporation retains a perpetual and legally recognised interest in the resources and environment of the area, even on land leased to residents. Land used to create dugout homes and businesses.

The 2015 Federal Court endorsement of the Barkandji claim fundamentally shifted the legal context. The grant of freehold title acts to extinguish native title, and so post-2015, the NSW Government could not legally proceed with its pre-existing promises of freehold conversion without undertaking complex and unlikely extinguishment negotiations with the Barkandji Corporation.

NSW was consequently compelled to offer an alternative tenure that was compatible with the determined native title rights, namely lease-hold options, viewed by residents as a devastating setback - the “final nail in the coffin” for their ownership dreams.

Dugout dwellers say the forced shift from promised freehold to a mandated leasehold tenure, eliminates the prospect of realising full property ownership and fails to properly reflect the market value of their homes.

The proposed leases also incorporate specific conditions which residents say are restrictive - most notably, the inclusion of a First Right of Refusal favouring the Barkandji Corporation.

That means, before any dugout can be bought or sold, it must first be offered to Barkandji Corporation, who may choose to purchase at the vendor’s asking price. It also means that for many years the town’s dugout owners have not been able to renovate their dugouts, and make safety improvements, such as fire escape tunnels, as negotiations over land use agreements and perpetual leases continue.

To add to the complex and often confusing nature of these ongoing negotiations, Central Darling Shire Council, the elected presentation of the White Cliffs community, went into administration in 2014, leaving dugout residents with no representation at the state government level.

A statement on the NSW Crown Lands website claims residents granted permanent leases in 2021.

“(This) was a significant outcome for the small opal mining community. The agreement was a ‘win–win’ that provided permanent security for White Cliffs dugout residents and due recognition of the Barkandji Aboriginal community and its traditional and enduring links to the land.”

I contacted another of Ken’s daughters Amber, who has been researching Native Title and legislation on many levels, in order to take on some of the stress placed on her father. She vehemently disagrees with the NSW Government’s assurance.

“The wording you’ve quoted from the Crown Lands webpage is one of the most misleading parts of this whole story, and has caused significant distress to the community. It gives the impression that every dugout resident received a fair, secure “permanent lease” in 2021.”

Amber claims that Leases can be terminated and dugouts forfeited with no compensation.

“The only additional ‘security’ provided is to allow us to appeal this decision after the fact,” she said. “These are people’s homes, built at their own expense, which many people have invested in for decades due to the long-standing agreement of freehold conversion.”

Amber says the dugout residents have written and gazetted evidence of this.

“(The offer of freehold tenure) is not in dispute, even by Crown Lands.”

Amber and Ken further stress that no leases were issued in 2021.

“The agreement referred to was the registration of the Indigenous Land Use Agreement (ILUA) between the State and the Barkandji people,” Amber explained.

“The leases themselves weren’t drafted until late 2023, nor finalised until late 2024, and included 40+ pages of terms and conditions (well beyond the six in the ILUA) Many are still unsigned as of now - more than a decade after the Native Title determination.”

Amber said many residents delayed signing the lease, or flat out refused to do so.

“Those who did sign, did so under pressure and fear of losing their homes. Several have since raised formal complaints about unclear terms, contradictory advice, lack of alternative options, and absence of any process to resolve safety issues.”

The dugout residents also claim there was no community consultation and that the ILUA between the NSW Government and the Barkandji people was negotiated and the lease drafted without any input from dugout residents.

“We only became aware of the details years later, when perpetual lease documents arrived in the post,” Amber said.

“The NSW Government has repeatedly failed to address problems. The August 2025 “project closed” newsletter triggered a formal Minister’s Briefing Pack from our family on behalf of my dad, Ken Harris. When that went unanswered, we lodged a renewed Ombudsman complaint in September outlining these inconsistencies.”

“The statement that it was a ‘win–win’ and that residents ‘were granted permanent security in 2021’ simply doesn’t match the facts on the ground. The community remains divided and many of the core safety and tenure issues are unresolved.”

At the time of publication, there has been no word on the status of the Ken Harris complaint to the Ombudsman.

The Barkandji corporation has been contacted for comment, as have Member for Parkes Jamie Chaffey MP and Member for Barwon Roy Butler MP.

Background to Native Title in NSW

The White Cliffs dispute cannot be understood outside the framework of the Native Title Act which was enacted in 1992, following the landmark Mabo High Court decision. The primary objective of the Act is to balance the interests of Indigenous and non-Indigenous people regarding land and waters by establishing formal processes for recognition and protection of native title.

Understanding the key terms in the White Cliffs land dispute

The dispute at White Cliffs involves complex legal and governmental terms. For context, here is a glossary of key definitions related to the land tenure, Native Title, and the ownership of the dugout homes:

- Native Title legalities: The laws and legal processes in Australia governing the recognition and protection of Indigenous peoples' rights and interests to land and water, established after the Mabo High Court decision and the Native Title Act of 1992.

- Freehold title: The most complete form of private land ownership, where the owner has perpetual ownership rights and is generally free to use, sell, or transfer the land. The NSW Government had previously assured dugout residents they would receive this type of title.

- Leasehold tenure: A form of land tenure where a person is granted the right to occupy or use a property for a specified period, subject to certain conditions, while the land itself is still owned by the Crown or another party. This was the alternative offered to White Cliffs residents instead of freehold.

- Extinguish native title: A legal action that permanently removes or cancels existing native title rights and interests over a specific area of land. Granting freehold title acts to extinguish native title.

- Barkandji Corporation: The organisation that represents the Barkandji First Nations people of the region. They lodged a native title claim which was determined by the Federal Court in 2015, confirming their non-exclusive rights and interests in the area.

- First Right of Refusal: A condition in the proposed leases stating that before any dugout can be bought or sold, it must first be offered to the Barkandji Corporation, who may choose to purchase it at the vendor's asking price.

- Indigenous Land Use Agreement (ILUA): A voluntary, legally binding agreement made between a native title group and other parties about the use and management of land and waters. The registration of the ILUA between the State and the Barkandji people occurred in 2021.

Back Country Bulletin accepts Letters to the Editor or story information at any time, via email – [email protected]

NEWS

COMMUNITY

RURAL

SPORT

VISIT OUTBACK NSW

VISIT BALRANALD