The road to nowhere: why the new 'Long Walk' movie is a brutal must-watch

Kimberly Grabham

13 February 2026, 7:00 PM

The Long Walk (2025) Review: Stephen King’s Dystopian Classic Hits the Screen

In Short:

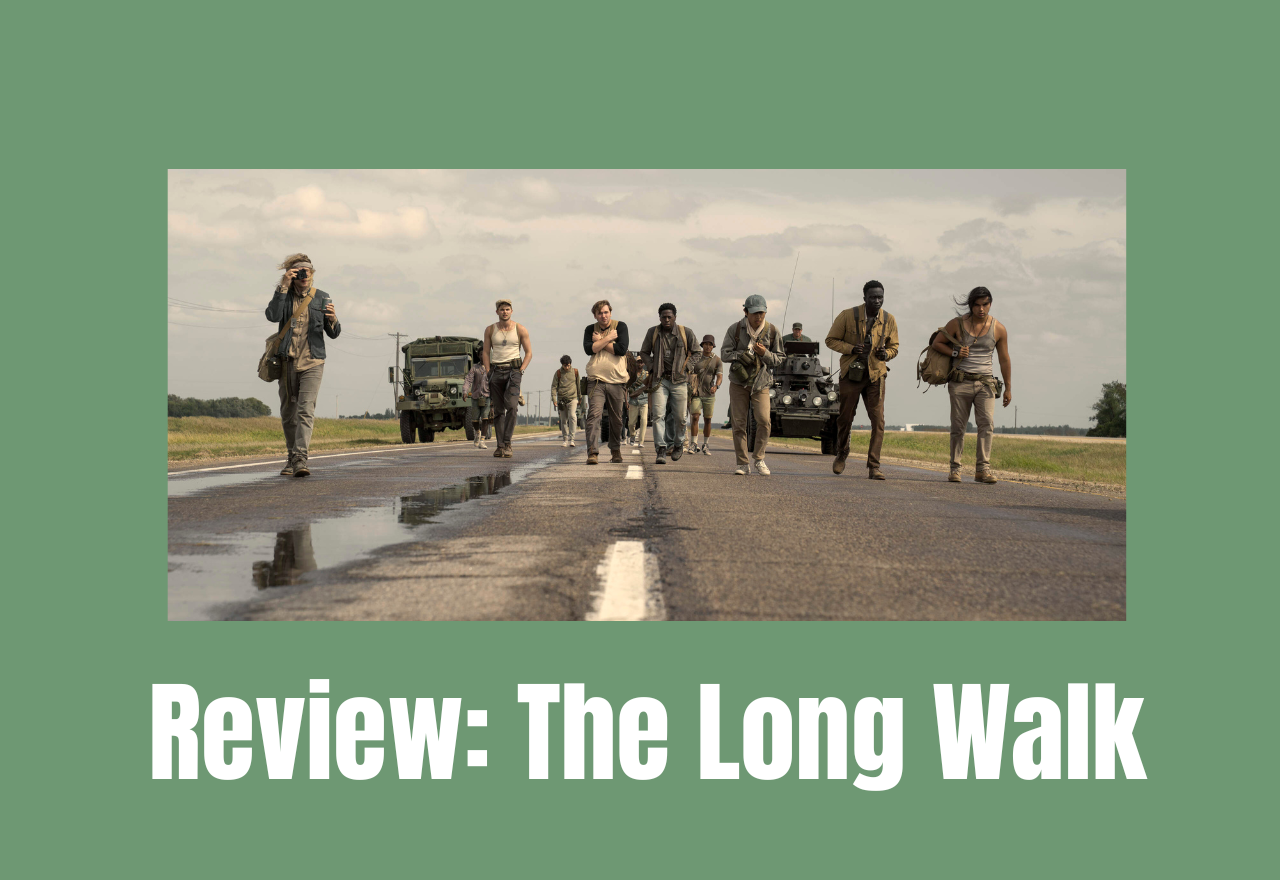

- The Rules: 50 boys walk at three miles per hour. Three warnings for slowing down, and the third is a death sentence. Only one survives.

- Cinematic Grit: Director Francis Lawrence (The Hunger Games) creates a claustrophobic, relentless atmosphere that captures the physical agony of the walk.

- Human Connection: Beyond the horror, the film shines in its portrayal of the "Musketeers", a group of boys who choose friendship and radical empathy in a system designed to kill them.

I read the Stephen King book, written under his pseudonym, Richard Bachman, The Long Walk a long time ago. I don't remember much of the ending anymore.

The details have softened and blurred the way they do with books you read in another life. But I remember the feeling. That slow, creeping, choking suffocation. The way King/Bachman built a world that pressed in on you from every side, with nowhere to look and nowhere to go. And I remember the warnings. First, second, third. The way each one landed like a physical blow. The way the finality of that third one hung over everything, every single step, like a guillotine blade you couldn't stop staring at.

Watching the 2025 film, that feeling came back immediately. And that, more than anything, is what makes this adaptation remarkable.

The set-up is deceptively simple, which is exactly how King intended it. In a dystopian, alternate-history version of America, somewhere in the grey, sweltering 1970s, fifty boys are chosen, one from each state, to participate in an annual event known as The Long Walk. They line up on a road. And then they walk.

That's it. That's the contest.

No arena. No weapons. No elaborate obstacle course or theatrical spectacle. Just a road stretching out ahead of them, and a set of rules so brutally straightforward they barely need explaining. The boys must maintain a pace of at least three miles per hour. Nonstop. No sleeping. No stopping. No stepping off the path. They walk through the day and into the night, and then through the next day, and the next night, and on and on until there is only one boy left.

If you fall below the pace, you receive a warning. A second warning if you don't pick it up. A third warning, and soldiers in armoured vehicles execute you on the spot, right there, right then, in front of everyone. No ceremony. No reprieve. No appeal. The ticket, as it's grimly referred to, is unrefundable.

The last boy walking wins a fortune and the fulfilment of one wish, anything he wants for the rest of his life. Which sounds magnificent, until you do the maths on what it actually costs to get there.

The film is overseen by the Major (Mark Hamill), a charismatic, unsettling figure who frames the Walk as a noble tradition; something to inspire the nation, to forge real men out of boys. Whether anyone actually believes that is another matter entirely.

King's novel has been considered, for decades, one of his most unfilmable works. And you can see why. There's no monster. No supernatural twist. No dramatic action set-piece to rally around. It's boys walking down a road, talking, and slowly dying. On paper, that's a brutal pitch for a film. On screen, in lesser hands, it could easily become exactly as boring as it sounds.

Francis Lawrence, the man behind the Hunger Games films, has done something genuinely difficult here. He's made stillness cinematic. The camera moves almost constantly, tracking alongside the walkers in a way that's fluid but relentless, pulling you into the rhythm of their steps until you can practically feel the blisters forming. Cinematographer Jo Williams keeps everything drenched in a kind of oppressive, amber-toned light that makes the whole thing feel airless and endless. The night scenes are particularly stunning, murky and claustrophobic, the road disappearing ahead into nothing.

And the details matter. The costumes and makeup do quiet, devastating work as the Walk progresses. The clothes get darker, heavier, soaked with sweat. The faces hollow out. The injuries accumulate, blisters, cramps, twisted ankles that bend into shapes ankles are not meant to bend into. You watch these boys wear down, mile by mile, and the film never lets you look away from what it's actually costing them.

The walkers are drawn from across the country, different states, different backgrounds, different temperaments, different reasons for being there. Some volunteered out of economic desperation. Some are running from something. Some, like the young Thomas Curley, appear to have lied about their age just to get in, which tells you everything about how few options some of these kids had before they ever set foot on that road.

And somewhere in the early miles, before the exhaustion has properly set in and the horror has fully landed, a small group of them find each other.

Ray Garraty (Cooper Hoffman) is our way into the story, quiet, warm, carrying something dark and personal that slowly comes into focus as the Walk progresses. He's the home-state representative, and he's left behind a tearful mother (Judy Greer) at the starting line who knows, with the clarity only a mother can have, what the odds actually are.

Ray falls in with a handful of walkers who become, quietly and without any grand declaration, the most important people in his life. There's Art Baker (Tut Nyuot), a gentle, devout young man from Baton Rouge who clutches a small Bible and wears his grandmother's cross around his neck. There's Hank Olson (Ben Wang), loud and talkative and full of bravado that starts to fray almost immediately under the weight of what they're doing. And then there's Peter McVries (David Jonsson), scarred, wise beyond his years, carrying his own damage quietly, and possessed of an almost stubborn insistence on finding light in the darkness around him.

The four of them dub themselves the Musketeers. (There are four of them - not three. They're aware of the irony.) And from that moment, the film becomes something far more interesting than a survival thriller.

This is where The Long Walk does something genuinely rare for a film like this. It doesn't rush the friendships. It lets them breathe.

You watch these boys talk, really talk—the way people only do when the stakes are so high that pretending doesn't seem worth the energy anymore. They argue about girlfriends and God and what they'd wish for if they somehow made it out. They trade stories. They bicker. They make each other laugh in the middle of something that should make laughing impossible. And slowly, without fanfare, they become the reason each of them keeps putting one foot in front of the other.

Cooper Hoffman brings a warmth and openness to Ray that anchors everything. But it's David Jonsson as McVries who is the quiet revelation of the film. McVries is the one who keeps choosing connection over self-preservation, who sees the people on the roadside not as vultures but as families, who tells Ray, when Ray is sinking into the darkness of his own rage, to find something worth walking towards instead. Jonsson plays it without sentimentality, without preaching. He just is McVries, and McVries is magnificent.

The bond between Ray and Pete becomes the emotional spine of the film. It's not flashy. It's not dramatic in the way Hollywood usually demands. It's two young men walking side by side, talking, and holding each other up. And because the film takes its time with it—because Lawrence trusts the audience to sit with it—it lands with a weight that catches you off guard.

Their conversations carry an incredible amount of emotional weight. As we begin to realise that either of them could die at any moment, their friendship feels like an act of resistance.

That's exactly it. In a system designed to make them competitors—designed to ensure that for one of them to survive, every other person on that road must die—choosing to care about someone is quietly, stubbornly radical. The Musketeers don't just walk together. They shield each other. They risk their own warnings to help a struggling walker keep pace. They make pacts about looking after each other's families. They sit with each other in the dark and say the kinds of things you'd never say if you thought you had forever to say them.

And when the Walk takes them, one by one, because it will, because it always does, the grief is devastating precisely because the joy was real.

Stephen King's work has a complicated relationship with the screen. For every Shawshank Redemption or Stand By Me, there's been a dozen adaptations that missed the point entirely, that took the horror or the spectacle and lost the humanity underneath. King writes people. That's what he does. The monsters and the magic are just the frame. The real story is always about what it means to be alive, and afraid, and trying to connect with another person anyway.

The Long Walk is one of the purest expressions of that, and Francis Lawrence has understood it. He hasn't tried to make the film bigger than it is. He hasn't added explosions or love interests or third-act twists to goose the pace. He's trusted the premise, trusted the performances, and trusted the audience to sit with something slow and uncomfortable and genuinely moving.

The result is a film that does what the best King adaptations do; it takes something that lives in your chest, that queasy, helpless, can't-look-away feeling, and puts it up on the screen, exactly where it belongs.

The Long Walk is not an easy watch. It shouldn't be. It's a film about boys dying, and it doesn't flinch from that. But it's also, underneath all of that, a film about what happens when human beings reach for each other in the worst possible circumstances, and find that it's enough. That it might, in fact, be the only thing that ever was.

If you read the book and you loved it, you'll find something faithful and deeply felt here. If you haven't read it, you'll find one of the most quietly devastating films of 2025. Either way, you'll find yourself thinking about it for a long time afterwards.

Not about the warnings. Not about the road. About the boys who walked it together.