The gamble on tomorrow: Southern Cryonics and the long shot at life

Kimberly Grabham

28 July 2025, 2:00 AM

Picture this: it's a July afternoon near Holbrook, and inside a nondescript shed surrounded by high fencing, two people lie suspended in liquid nitrogen at minus 200 degrees Celsius. They're not dead, exactly – at least, not in the way their families see it. They're waiting.

The Melbourne woman who became Southern Cryonics' first client died in hospital on July 4 from chronic illness.

Within minutes, the facility's staff were there, packing her body in iced water for the journey that her family hopes isn't final.

Six hours later, after a careful cooling process involving 250 kilograms of specialist equipment, she was sealed in her cryogenic chamber in what used to be farmland on the outskirts of town.

It sounds like science fiction, and to many experts, that's exactly what it is.

The early days of cryonics were nothing short of horrific – bodies crammed into capsules like puzzles, left to thaw when funding ran out, eventually scraped from containers as "tissue sludge."

The first cryonics operations in California and New Jersey in the late 1960s were disasters that would make a horror film director wince.

"At the moment, cryopreservation is limited to individual cells and very simple tissues. We can't even store a single organ by itself," says RMIT's Saffron Bryant, a cell and tissue cryopreservation expert who's deeply sceptical about the whole enterprise.

The science is brutally simple: when water inside cells freezes, it expands and causes damage.

Scientists use special chemicals called cryoprotective agents to reduce ice formation, but whole organs are made up of different types of cells – different sizes, different shapes, all behaving differently. "You can't cryopreserve them all in the same way," Dr Bryant explains matter-of-factly.

One cryobiologist compared the idea of reviving frozen humans to "believing you can turn a hamburger back into a cow."

If we could freeze organs successfully, we'd already be solving the organ donor shortage that costs lives every day.

But Peter Tsolakides, the former marketing specialist who founded Southern Cryonics after reading about it as a teenager, isn't deterred by the odds or the ghoulish history. Standing in his facility that resembles "very large thermos flasks," he acknowledges the long shot they're all taking.

"Let's say that it's possible but very unlikely – say it's 10 per cent possible," he says, adjusting his glasses.

"You got 10 per cent possibility of living an extremely long life versus being buried underground or burned. Which one would you choose?"

His 32 subscribers, who pay $350 annually and have committed to the $170,000 suspension procedure, range from 15-year-old kids to 95-year-old pensioners.

"We have doctors to bus drivers," Tsolakides says with obvious pride. "Most of the people want to live very long lives, not necessarily be immortal. They're also interested in seeing what the future is."

It's tempting to dismiss this as expensive fantasy, especially given the grotesque failures of early cryonics. But history has a funny way of making fools of the sensible majority, even when the initial attempts are disasters.

Take heart surgery. The first attempts to operate on beating hearts in the early 1900s were catastrophic failures that killed patients on the table.

The medical establishment declared it impossible – you simply couldn't cut into the engine of life and expect it to keep running.

Yet by the 1960s, heart transplants were making headlines, and today we routinely stop hearts for hours during surgery, cooling bodies down to buy precious time.

Or consider continental drift. When Alfred Wegener suggested in 1912 that continents actually moved around the planet, the scientific establishment thought he'd lost his mind.

The idea was so preposterous that geologists ridiculed it for decades. It wasn't until the 1960s, long after Wegener's death, that plate tectonics proved him right.

Germ theory faced similar resistance.

For centuries, doctors believed disease came from "bad air" or just spontaneously appeared.

When Ignaz Semmelweis suggested in the 1840s that doctors should wash their hands between patients, his colleagues were so offended they had him committed to an asylum, where he died.

Louis Pasteur faced similar ridicule when he proposed that microorganisms caused disease.

Even anesthesia was controversial when it first appeared.

Many thought it was unnatural to undergo surgery without pain, while others feared the unknown risks of these strange new drugs.

Today, the idea of surgery without anesthesia seems barbaric.

The pattern repeats: vaccines were considered dangerous tampering with God's will; X-rays were dismissed as parlour tricks; Alexander Fleming's accidental discovery of penicillin sat largely ignored for years because no one could quite believe a mould could cure infections.

More recently, researchers discovered that Viagra helped hamsters adjust to new time zones 50 per cent faster – hardly what Pfizer had in mind when developing a heart medication.

And in 1990, a doctor cured someone's persistent hiccups using digital rectal massage, earning an Ig Nobel Prize for proving that medical breakthroughs can come from the most unexpected places.

The difference between then and now is that Tsolakides has learned from cryonics' horror-show past.

Unlike the early cowboys who left bodies to rot in cemetery vaults, Southern Cryonics operates with meticulous attention to detail.

The chambers hold a two-month supply of liquid nitrogen, monitored several times weekly. Multiple suppliers ensure continuous delivery. The facility has backup systems and detailed protocols.

Of the dozens of people frozen in those early disasters, only one remains preserved today: Robert Bedford, sealed into a Dewar in 1967. His family took custody of the capsule and meticulously cared for it at their own expense, eventually transferring him to Alcor, one of the modern cryonics companies that learned from those early failures.

The legal implications alone are mind-bending. If someone frozen today were successfully revived in 2150, they'd have been legally dead for over a century. Could they reclaim property that had passed to heirs? What about spouses who remarried? As one legal expert noted, we'd need to completely reinvent inheritance law.

Then there's the human cost.

In the recent British case of a 14-year-old girl with terminal cancer, her father objected partly because she would wake up, if she ever did, alone in a foreign country with no friends or family, centuries after everyone she knew had died.

"It's possible that something could go wrong," Tsolakides acknowledges, referring to the facility's dependence on regular maintenance and deliveries.

The suspension agreement his clients sign is brutally honest about the risks: if the company goes broke, gets shut down, or if cryonics becomes illegal, Southern Cryonics may simply "dispose of the patient's body by burial, cremation or transfer."

Legally, there's no special protection for the cryogenically frozen. In the eyes of Australian law, they're simply remains, and Southern Cryonics is classified as a cemetery by Greater Hume Council.

Health experts have described the sector as "Star Trek in play," and it's hard to argue with that assessment.

The science fiction comparison isn't unfair – we're talking about reversing death itself, something that's been the realm of fantasy for all of human history.

Yet that's precisely what makes it interesting.

Every scientific breakthrough started as someone's impossible dream, often built on the rubble of spectacular early failures.

The heliocentric model was heretical nonsense until it wasn't. Continental drift was geological madness until it became the foundation of modern geology. Hand-washing was medical blasphemy until it became the cornerstone of infection control.

The Southern Cryonics facility represents more than just an expensive insurance policy against death. It's a monument to human optimism – the stubborn belief that the impossible might just be improbable, and that the future might hold solutions we can't even imagine today.

The science, frankly, looks terrible. The early history was nightmarish.

The legal complications are staggering. But so was heart surgery once.

So was the idea that invisible creatures could make you sick.

So was the notion that continents drift around like rafts on an ocean.

Whether Tsolakides and his clients will ever see that future is anyone's guess.

The odds, as he admits, are probably terrible.

But as he stands among his "very large thermos flasks," he's betting on the same thing that's driven every great scientific leap: the possibility that tomorrow's breakthrough is just around the corner, even if today's attempts end in spectacular failure.

For now, two people wait in their liquid nitrogen chambers near Holbrook, suspended between death and an uncertain tomorrow.

Their families have made peace with the long odds, choosing hope over certainty, possibility over finality.

Time, as they say, will tell. And unlike those early disasters in California cemetery vaults, at least they'll be properly maintained while they wait.

Southern Cryonics is located near Holbrook, NSW. More information is available through their website for those interested in learning more about cryonic suspension.

NEWS

SPORT

RURAL

COMMUNITY

JOBS

VISIT BALRANALD

VISIT HAY

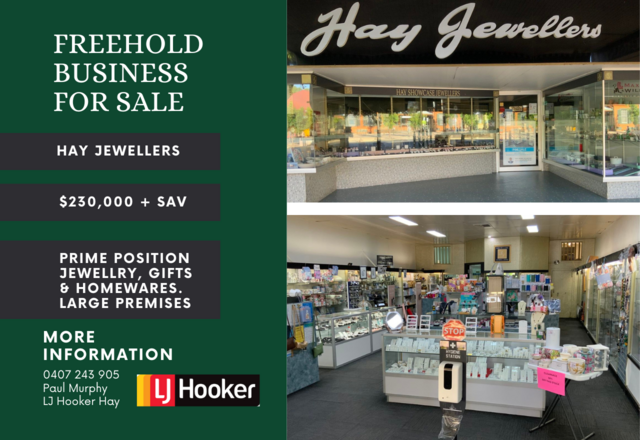

FOR SALE

COMMERCIAL PROPERTY