Living authentically: John Clissold’s journey home

Kimberly Grabham

08 January 2026, 4:00 AM

When we strip the unnecessary accoutrements of life away, what really matters is how we treat people, and if we have lived life in a way where we will be without regret. I am certain my lovely new friend John Clissold has achieved this; loved without prejudice, care without fear and lived life exactly the way he’s wanted.

At 80 years young, or as he prefers, ‘67 and some summers’, John Clissold sits in his Hay home, the rainbow flag visible from the street when he first moved in, a symbol of a life f inally lived on his own terms. Born in Broken Hill in 1945, John’s early years followed a conventional path.

His father was a metallurgist, his mother a school teacher. The family moved to Quorn, outside Port Augusta, before John moved to Adelaide for school. He spent over 40 years in the public service as an admin officer in the TAFE system, working across various campuses throughout Australia.

“I had a fairly good life, I have no regrets,” John reflected. But beneath the surface of this seemingly ordinary existence, John was hiding a fundamental truth about himself. From the age of eight, John knew he was different. “I always knew I was different from other blokes, other people,” he said. But growing up in the 1950s and 60s, being openly gay wasn't just discouraged, it was dangerous.

“You couldn't come out in the 60s. You'd get beaten up and probably killed,” John explained matter-of-factly. So, he did what society expected. He married, twice, and had children.

He hid behind society’s expectations of what men do, living a life that wasn’t truly his own.

It wasn’t until John was 57 years old that everything changed. After decades of living according to others’ expectations, he made the decision that would define the rest of his life; he came out. “I decided I wanted to be who I was,” John said simply, though the simplicity of those words belies the enormity of the decision.

“I’d hidden behind society’s expectations of what men do.” He left his young wife and two young children; one wasn’t quite one year old. He left her the house, the car, everything. He went to the southeast for TAFE work and stayed there for three or four years before returning to Adelaide. When he told his mother he was getting divorced, her response was pragmatic, “Why this time?” “I’m coming out,” John told her.

“Why didn't you tell me when you were growing up?” she asked.

It was a question with a good answer. “Most kids think they’ll get rejected by their families,” John explained.

“And there’s a lot of kids who do get rejected by their families and tossed out of home.” After coming out, John met Graham. “He was HIV positive, and he tried HIV drugs, which made him even sicker than he was originally,” John recalled. At a time when HIV/AIDS carried enormous stigma, when hospital staff wore full hazmat gear to attend to HIV patients, John's response to learning about Graham’s status was simple compassion. “I just took his face in my hands and said, ‘It doesn’t matter,’” John remembered. They’d always practised safe sex. What was the problem?

“He said, ‘You don't mind?’ Graham’s relief was palpable.” John became involved with People Living with HIV/AIDS, volunteering at their community centre in Glenelg, helping to serve lunches and spending time with people at a time when society largely shunned them. Tragically, after seven years together, Graham died of a heart attack. John came home to find him dead on the f loor, a trauma that still resonates decades later. In 2012, John met Michael at what he calls the men’s club, the gay sauna in Adelaide. “He always said, ‘I know how you got me. You stuck your foot out and I couldn’t get past. I had to sit down,’” John said, laughing at the memory. They hit it off immediately and would be together until Michael’s death earlier this year. Remarkably, they never had an argument in all those years. “If I started, I’d just walk away,” John said. “I’d go, ‘This isn’t going to work, is it?’ So, we’d just sit down and we’d talk.”

The connection went deeper than they initially realised. Michael’s mother had been born in Broken Hill, like John. They later met a philanthropist woman who had been born the day before John, also in Broken Hill. The threads of their lives had been intertwined long before they met. It was Michael and John’s travels that first brought them to Hay. “We used to travel through this town at least twice a year,” John recalled. They’d go from Adelaide across the plain to Griffith, stopping in the little town of Hay along the way. “The people in this town were very welcoming,” John said warmly.

They loved the Rainbow on the Plains festival so much that they made a decision that would impact the community for years to come.

Someone mentioned needing to buy tickets for festival events. “I thought it was all free,” John said.

After discussing it with Michael, they decided to donate $2,000 to establish what they called the Gay Nomads Gift, funding specifically for young people aged 17 to 25 who didn't have the money to attend Rainbow on the Plains events. “Every year I top it up,” he said. It’s his way of supporting his people, as he calls them. In 2022, John and Michael got married, a celebration of their decade together.

But it came after years of challenge. In 2017, Michael was diagnosed with non Hodgkin’s lymphoma. He went into remission, but the reprieve was temporary. In 2018, Michael was diagnosed with dementia, Alzheimer's disease. It ran through his family, his grandfather had it, his mum, his older sister, his brother. “And then he got it badly,” John said quietly. “I looked after him at home for as long as I could.”

When a place became available at Resthaven, part of the Uniting Church’s care services, John made the difficult decision to move Michael there. He gradually went downhill. On May 3 this year, Michael died. “The only thing that scared me on our wedding day was Michael came outside and looked around and said, ‘What are all these people doing here?’

And I would have had to say, ‘Well, we’re getting married today.’ He might have said, ‘Well, no, I’m not,’ and walked back inside. That was the only thing that scared me on that day.” Despite the difficulties, or perhaps because of them, they grew closer in those last couple of years. “That’s what life’s all about," John reflected.

“Finding somebody you love, and it’s not about sexuality or gender or anything like that, that’s your person. You are just together.”

Today, Michael sits in an urn in John’s bedroom. “We still have a natter,” John said with a smile.

After Michael’s death, John decided to do something for himself. At his fabulous party at the Services Club, people kept asking, “When are you buying a house? When are you coming back to live here?” So, he bought his house in Hay, “the best house in Hay,” as someone at the club told him.

The welcome he’s received has been everything he hoped for and more. At the club, people come up to say how pleased they are to have him there.

“The welcoming and the family-like quality that Rainbow on the Plains has developed out of nowhere is something magical,” John said. “In Adelaide, I must have had 20 good friends.

"Here, I’ve got maybe 20 good friends, and they all want me here. This is where I want to be.” John’s involvement with the Sisters of Perpetual Indulgence, the drag nun order that participates in Rainbow on the Plains, began after Graham’s death and has become an integral part of his identity in Hay. His first parade was memorable for multiple reasons.

At the end of that first parade, all the sisters jumped into the pool. “The only problem with a habit, a nun’s habit, is that there’s so much material. And when you go in the water, it gets a lot heavier and it goes right over the top of your head as well. “I’m flapping in the pool thinking,

“Bugger, I’ve got my phone in my pocket.” Ever practical, John has already planned his burial. He wants a natural burial, standing up. “It saves on space,” he said with characteristic pragmatism.

“You just need a posthole digger.”

He’s discussed it with someone on the council, who’s going to put it to the committee. If they can’t accommodate his wishes in Hay's natural burial ground, he’ll buy an acre off a farmer and be buried on their land. “I want to die at home, with my friends around me. Maybe my family will come from Adelaide. We’ll have a fabulous time. I’ll pay for you all to go out for a meal.” When asked what message he’d like to share, John doesn't hesitate.

“Be who you want to be. Live how you want to live.

“If your parents or your friends don’t like the way you are, it’s not your problem. It’s their problem.” It’s advice born from decades of hiding, followed by decades of freedom. At 80, John has the clarity that comes from having lived both ways, according to others’ expectations and according to his own truth. His relationship with his ex-wife has evolved over the years. “She and I are good friends now,” John said. She’s told him she was too young and too narrow-minded back then. “She said, ‘I didn’t realise that gay people can be married but still have separate lives.

We could have done that and we could have co parented our children’.”

It’s an observation that speaks to how much society has changed, and how much further there still is to go. John’s house in Hay, with its 51 solar panels and plans for a native garden out front, is more than just a house. It’s a statement. The rainbow flag flying outside isn't just decoration, it's a declaration that after 57 years of hiding, John Clissold is finally, fully, unapologetically himself.

“Gay people need more affirmation than we actually get,” John reflected.

It’s why the Gay Nomads Gift matters so much to him. It’s why he’s open about his story. It’s why he lives authentically, visibly, in a small country town. “If anybody who reads this needs help, come and talk to me,” John offered. “I live in Hay.” It’s a simple invitation, but it carries the weight of a lifetime of experience; the struggles, the losses, the loves, and ultimately, the hard-won freedom to simply be himself.

At 80 years young, John Clissold has finally found home. And in finding it, he’s helping others find theirs too.

NEWS

SPORT

COMMUNITY

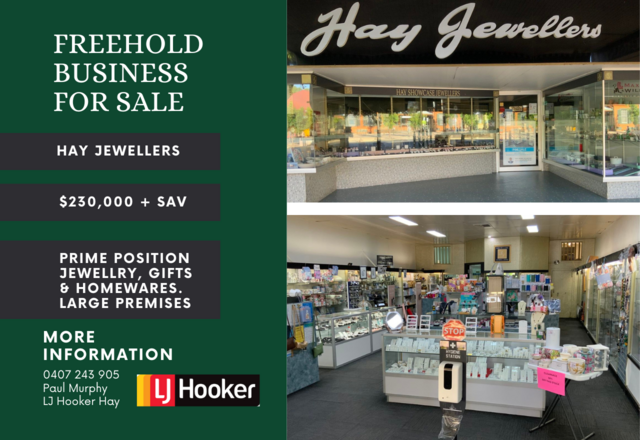

FOR SALE

COMMERCIAL PROPERTY