Chinaman Charley’s fate

Kimberly Grabham

25 December 2025, 10:00 PM

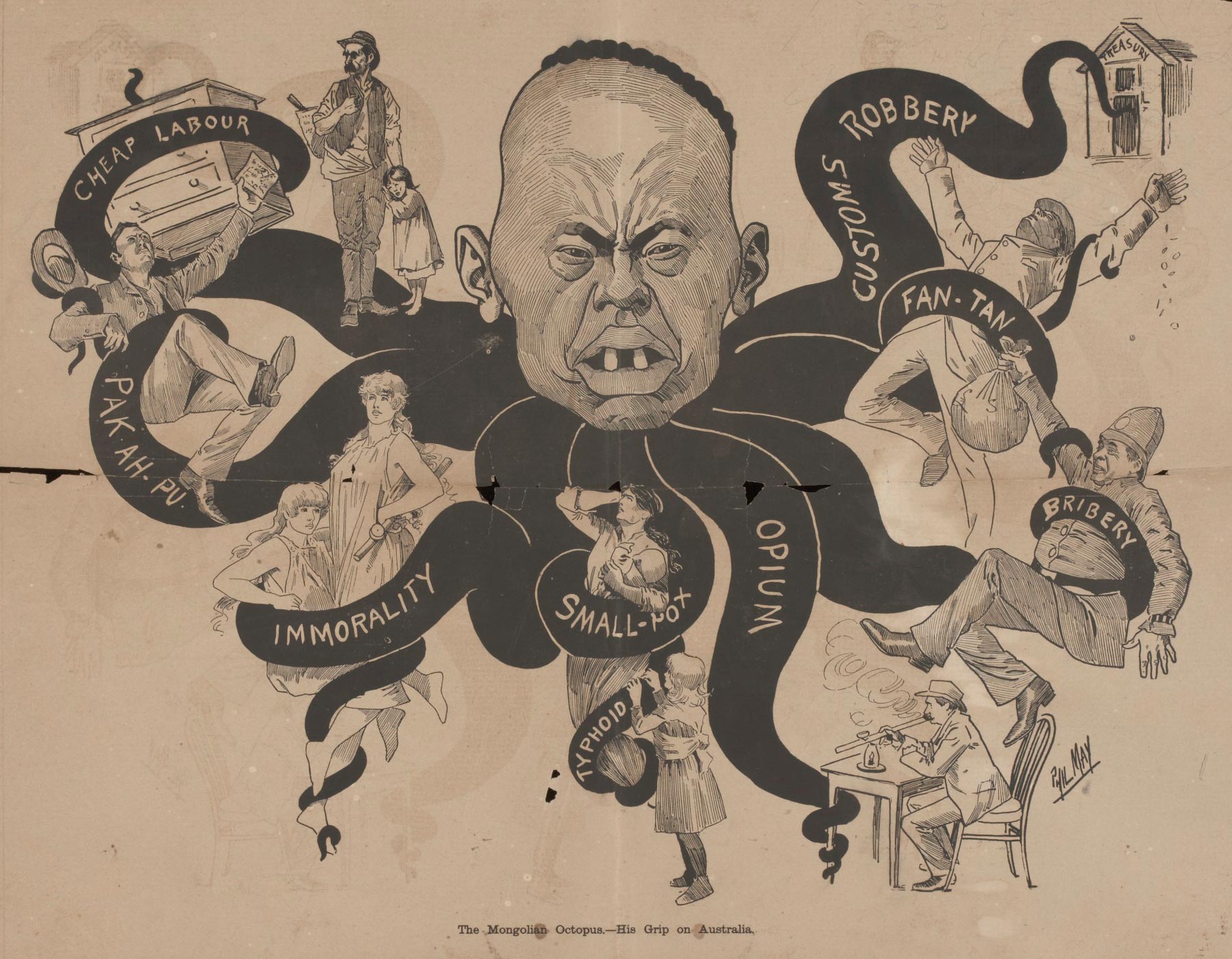

The Bulletin, 21 August 1886. The image shows the head of a person depicted as an octopus with eight tentacles. Each tentacle is holding a person or object with text written on each tentacle.

The Bulletin, 21 August 1886. The image shows the head of a person depicted as an octopus with eight tentacles. Each tentacle is holding a person or object with text written on each tentacle.The information used to create this recount of murder on Wyndowinal Station, and the resultant detaining of the suspect at Balranald lock up, was published in the Pastoral Times, Deniliquin Newspaper on Saturday July 10, 1875.

The headline read, SUPPOSED MURDER (FROM OUR OWN CORRESPONDENT.)

It details depositions taken at a magisterial inquiry held by R.B. Mitchell, Esq., P.M. at Wyndowinal Station, on Sunday, June 27 1875, concerning the death of George Adams, who died at that station the night before.

Phillip Bennett Moon

Phillip Bennett Moon, superintendent of Wyndowinal Station, was the first of three people to make a statement under oath.

“I recognise the body to be that of a man called George Adams, who was a cook in my employ.,” Moon said.

“I last saw him alive yesterday morning, 26 June instant. The man was then to all appearance in robust health.

“He was a man about forty years of age, and, so far as I am aware, of sober habits. I never knew him to be subject to fits of any description. As a rule, the man is known to be quarrelsome with other men in the kitchen. He was not a man that made friends.”

“A Chinaman, known by the name of Charley, has been messing in the kitchen with the cook for the last three days; both of them used to have their meals together, and he has been the only one during this time messing with the cook.”

Moon had discovered the death of Adams when he received a letter while he was at Waldaira Station, sent by William O’Hara, along with allegations detailed in the letter, that the ‘Chinaman Charley’, had poisoned him.

The Police Magistrate for the district was at Waldaira at the time, Moon shared the news with him, and the pair immediately left for Wyndowinal.

William James O’Hara

William James O'Hara, 21, lived at the station, and was engaged as a youth learning colonial experience. His testimony was quite lengthy, having had the most interaction that evening with Adams, before and after he exhibited signs of illness.

As O’Hara was suffering from a headache on June 26, he was at the station all that day.

“I was not out on the run, and I had frequent opportunities of seeing the cook during the day,” he said in his testimony.

“The cook was busily employed all day scrubbing rooms in the house. He gave me my dinner as usual about one o'clock, and at about a quarter past six o'clock he brought me in my supper.

“At that time, nor during any part of the day, the cook did not complain of any illness. A little after seven o'clock the cook cleared the things from my table.”

After Adams had taken away O’Hara’s supper dishes, O’Hara laid on the sofa for fifteen minutes. The cook came back in, and asked the younger man if he was going to sleep there all night. O’Hara said no, and then noticed that Adams had a plate in his hand.

“He came over to me, and, pushing the plate right under my nose, said with great excitement, "The bastard Chinaman has poisoned me!" I jumped up and advised the cook to swallow an emetic at once,” O’Hara reported in his deposition.

“The cook put the plate into the cupboard, and said, “Keep this and get it analysed, for I will be dead in the morning.”

Adams went back to the kitchen, and came back in five minutes yelling to O’Hara to get him an emetic, and that his legs were failing him. He then collapsed, saying that he had been poisoned.

“I asked him what proof had he that the Chinaman had poisoned him,” O’Hara said.

“He said that when he left the kitchen the first time to clear away the things his turnip-tops were all right, but that upon his return they were as bitter as gall.”

O’Hara then carried Adams into the kitchen, undressed him, and put him to bed. At this time, Adams was still conscious, and accusing the Chinaman of poisoning him.

“I did not see the Chinaman during all this time — he seemed to keep out of the way,” O’Hara said.

“I gave Adams two emetics; he swallowed both of them, each one consisted of a small cup full of warm water, with a teaspoonful of mustard therein mixed.

“The man vomited some turnips, and also, I think, what appeared like sauce (tomato sauce is in the kitchen); he told me while lying on his bed that the Chinaman dished the turnips for the kitchen, and pressed the water from them with the lid of the saucepan; he did not tell me whether the Chinaman had eaten any of them likewise.”

Adams died in the presence of O’Hara, beginning to suffer from strong convulsive fits, drawing his body up to his head, and vomiting at the same time, with hard spasmodic breathings at intervals.

“The poor man died at last seemingly from exhaustion,” O’Hara said.

“A few minutes before his death he asked me to turn him round, and in the act of doing so he died. The saucepan that the turnip-tops were boiled in was made of iron, and not of copper. I made a hearty meal of the turnip-tops at supper.”

O’Hara reported in his testimony that Adams died an hour and a half from the time he brought O’Hara the plate of the turnip-tops, and first said the Chinaman had poisoned him.

“I heard the Chinaman and the cook talking together in an angry tone on Friday night, the night before the cook suddenly died,” O’Hara said.

O’Hara was the second person to report that Adams was of a ‘quarrelsome disposition’, and had fought with two men on the station, besides the Chinaman, and that Nobody, with the exception of the Chinaman, messed (worked) with the cook for three days up to his death.

“After Adams died, I brought the Chinaman into the kitchen, and showed him the dead body of his recent messmate. The Chinaman cried very much.

“Whilst the cook was dying. I heard the Chinaman make a noise as if trying to vomit. He was in a hut about ten yards from the kitchen, and the dying man made a remark that it was the Chinaman's cunningness.

“The Chinaman did not come to see the cook whilst he was dying. Stewart also made the name remark when he heard the Chinaman attempting to vomit, that it was cunningness that prompted him to do so.”

The Chinaman goes by the name of Charley, has only been three days on the station, and is employed as gardener. I have never heard Adams complain that he was ever subject to fits. He has told me that he has been a great drunkard in his time, but he could obtain no liquor on the station.

William Stewart

By the time that William Stewart, a carpenter residing on Wyndowinal station, came across the incident, Adams had already been put to bed by Mr O’Hara, and this is, where Stewart’s testimony began.

Adams, Stewart claimed, had said to Stewart that he was very ill, and told him the Chinaman had poisoned him.

“I asked him how, and he said, I had some cabbage, and whilst I was out with Mr. O’Hara, I believe be (alluding to the Chinaman) put some poison into it,” Stewart said.

“I then went and had a cup of tea, and on my return, I found Adams very sick and throwing up.

“When I went into the hut where the Chinaman was, I saw the Chinaman pretending to be sick.”

Stewart is allowed to make his own conclusions in the statement, as he claims to have searched for evidence of the Chinaman vomiting, and found none.

Stewart reported that Adams remained quite sensible up to his death, and more than half-a-dozen times said to him that he had been poisoned by the Chinaman.

“I went to bring the Chinaman face to face with Adams, but upon my return with the Chinaman Adams was dead,” Stewart said.

“As he lay dead, I said to the Chinaman " What have you been giving that man?" and he replied that cabbage made him sick, that he (the Chinaman) also ate a little of it, but found it very bitter, and threw it out of his mouth."

“The Chinaman cried very much, and wanted to explain that he did not do it, but the Chinaman cannot speak English so as to be understood.”

The Pastoral Times article said that the Police Magistrate decided that his opinion was that Mr George Adams died from murder by poison, administered to him by one Charley, a Chinaman, and he ordered Charley, the Chinaman into custody upon suspicion of murder by poison.

Due to the isolation of Windowinal, an immediate post mortem examination was not possible.

The Police Magistrate ordered the plate of turnip tops to be sealed up in his presence, all of the vomit from the victim be scraped up and collected, and the deceased to be temporarily buried, with an exhumation being conducted at a later date if required.

‘Chinaman Charley’ committed suicide in the Balranald lock up before any formal investigations could be made, and concrete conclusions drawn in the case. Was it guilt or despair that drove him to commit that act.

Mr Adams was, according to the depositions of all witnesses, a quarrelsome man who was not well liked, and had altercations with at least two other people on the property. Adams and Charley were heard by O’Hara, the 21-year-old, arguing Friday, the night before the murder.

Chinaman Charley was on the property a short time, three days, according to the testimony of Mr O’Hara. Nobody saw Charley committing the act, it was an assumption made by Adams, who did not elaborate on the reasons why he would assume it was indeed Charley.

Is three days a long enough time for a grudge or quarrel to drive a man to murder, or did someone see the opportune circumstances and decide to take action, and blame it on ‘Chinaman Charley?’

A mystery which, unfortunately, will never be solved.